Liver Phase I and Phase II Detoxification Pathways

The biochemical mechanisms of xenobiotic metabolism and transformation

Introduction to Hepatic Metabolism

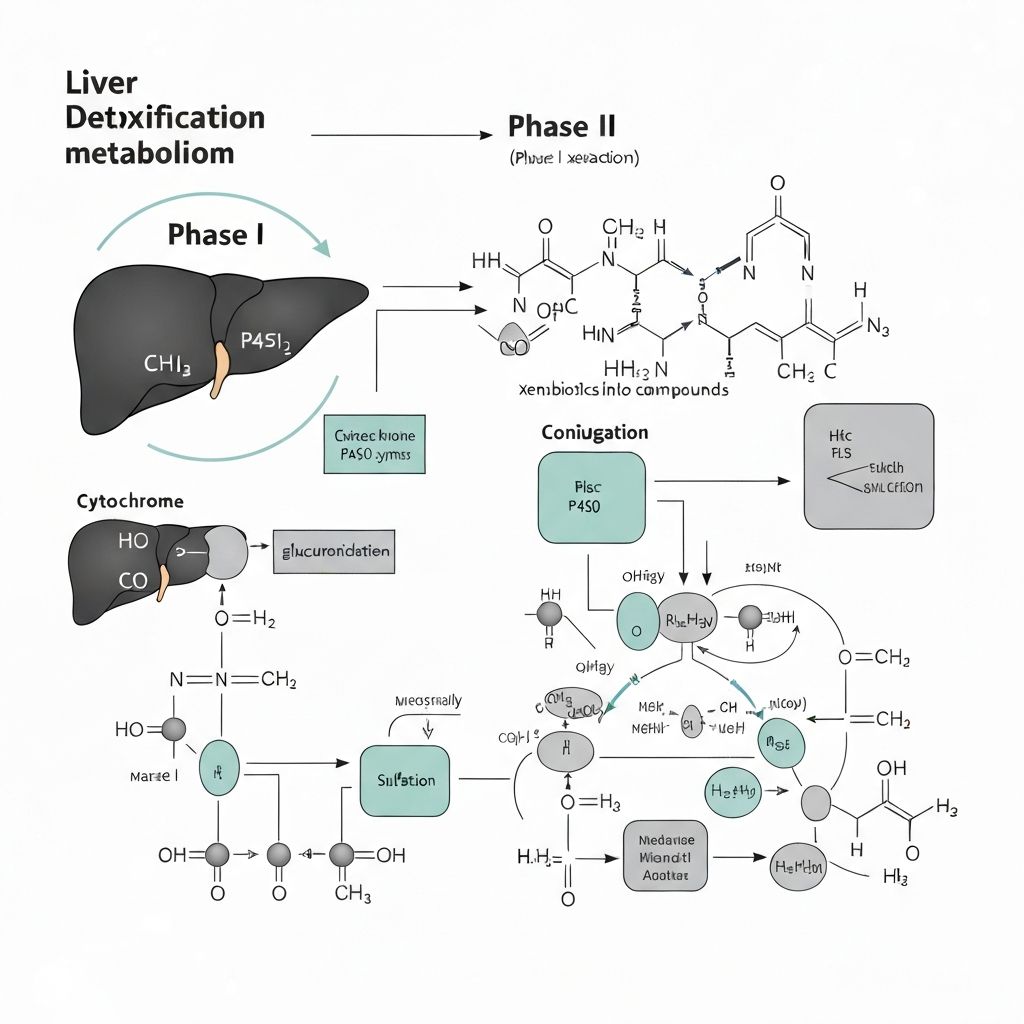

The liver is the primary organ responsible for processing foreign chemical compounds. These compounds, called xenobiotics, originate from food, environmental exposure, pharmaceuticals, and industrial chemicals. The liver systematically transforms these substances through enzymatic pathways known as Phase I, Phase II, and Phase III metabolism, enabling their elimination from the body.

Phase I Metabolism: Oxidation and Modification

Phase I metabolism represents the first enzymatic transformation of xenobiotics. This phase modifies the chemical structure of foreign compounds, making them more polar and susceptible to further processing or direct elimination.

Cytochrome P450 Enzyme System

The primary enzyme family responsible for Phase I reactions is the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system. These monooxygenases catalyze oxidation-reduction reactions that introduce or expose functional groups on xenobiotic molecules. The most abundant CYP enzymes include:

CYP3A4/5

Metabolizes approximately 50% of all pharmaceutical drugs and many dietary compounds. These enzymes are highly expressed in hepatocytes and intestinal epithelial cells.

CYP2D6

Metabolizes many psychotropic medications, beta-blockers, and antiarrhythmic drugs. Shows significant genetic variation among populations.

CYP2C9

Metabolizes NSAIDs, warfarin, and other commonly used medications. Also shows genetic polymorphisms affecting drug metabolism rates.

Oxidation Reactions

Phase I oxidation typically introduces hydroxyl (-OH) groups or removes carbon chains, increasing polarity. These reactions can activate or deactivate compounds depending on the molecular structure. Some Phase I metabolites are more reactive than their parent compounds and require rapid Phase II conjugation.

Phase II Metabolism: Conjugation and Excretion

Phase II metabolism involves the attachment of water-soluble molecules to Phase I metabolites or native xenobiotics. This conjugation dramatically increases hydrophilicity, facilitating excretion through urine or bile.

Glutathione Conjugation

Glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) catalyze the attachment of reduced glutathione (GSH) to electrophilic compounds. This represents one of the most abundant Phase II pathways. The resulting glutathione conjugates are subsequently processed by gamma-glutamyltransferase, dipeptidases, and N-acetyltransferase, ultimately forming mercapturic acids that are excreted in urine.

Glucuronidation

UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) catalyze the attachment of glucuronic acid, derived from UDP-glucuronic acid, to hydroxyl, amino, or carboxylic acid groups. Glucuronidation produces highly water-soluble metabolites that are readily excreted biliary or renally. This pathway is particularly important for metabolizing bilirubin, steroid hormones, and many drugs.

Sulfation

Sulfotransferases (SULTs) catalyze the transfer of sulfate groups from 3'-phosphoadenosine 5'-phosphosulfate (PAPS) to phenolic or alcoholic hydroxyl groups. This pathway shows limited substrate capacity compared to glucuronidation and GSH conjugation but is nevertheless critical for eliminating certain compounds including estrogens, catecholamines, and dietary phenolics.

Acetylation

N-acetyltransferases transfer acetyl groups from acetyl-CoA to amino groups, primarily in Phase II processing of compounds containing aromatic amines. The rate of acetylation varies among individuals due to genetic polymorphisms, creating fast acetylators and slow acetylators. This variation affects pharmacokinetics of certain antibiotics and other compounds.

Phase III Metabolism: Transport and Excretion

Phase III involves active transport proteins that facilitate the movement of metabolites from hepatocytes into blood and bile for systemic excretion or biliary elimination. These transport proteins include multidrug resistance proteins (MDRs), organic anion transporters (OATs), and organic cation transporters (OCTs). Without Phase III transport, even highly conjugated metabolites would accumulate within hepatocytes.

Genetic Variation and Individual Metabolic Differences

Genetic polymorphisms in Phase I, II, and III enzymes result in substantial variation in individual xenobiotic metabolism rates. Some individuals are slow metabolizers of certain compounds, while others metabolize the same compounds rapidly. This variation explains differences in drug response and tolerability among populations. However, this variation does not indicate "poor detoxification"—rather, it reflects normal human genetic diversity in enzyme expression and activity.

Continuous and Automatic Operation

These metabolic pathways operate continuously and automatically in all healthy individuals. They do not require external stimulation, supplementation, or special protocols to function. The body's detoxification capacity is constitutively active.

Related Articles

Renal Excretion

Learn more about kidney functionCommercial Detox Products

Review clinical evidenceInformation Context

This educational content explains liver detoxification biochemistry. It is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. For health-related questions, consult qualified healthcare professionals.